What Would Walt Disney Do? Part II—Disneyland 1976, the Team of Teams, and the Reckoning of Medical Ethics

By David E McCarty MD FAASM (…but you can call me Dave)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“When I started on Disneyland, my wife used to say, ‘But why do you want to build an amusement park? They’re so dirty.’ I told her that was just the point—mine wouldn’t be.”

--Walt Disney

“We wish you an enlightening experience—for, though your body will shrink, your mind will expand.”

— Adventure Thru Inner Space, Disneyland, 1967 (narration by Paul Frees) DisneyParkScripts.com)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Walt Disney: THE ONE

In a recent essay, I spilled my guts about my lifelong Southern Gothic love affair with an integer, my curious long-term bromance with the number FIVE. I ached on and on about FIVE’s humanity and pioneering energy and even revealed (gasp!) that one’s birthdate can resolve to a single number and that—wonder of wonders!—mine resolved to FIVE!

Recalling just in time that this essay series is entitled WHAT WOULD WALT DISNEY DO? I opted to put ol’ Walt’s birthday to the test: December 5, 1901.

Oh, there’s mercurial FIVE energy there—I see you, 5th of December! There’s THREE energy, too (December’s month 12 resolves 1+2 to 3)--which is considered by nerdy numerologists to be a creative glimmer. You can look that up.

But the full date—12/5/1901--resolves down to a single digit, and for Walt Disney, it couldn’t have been anything else, when you think on it, hard enough.

Yup. No question.

Walt Disney was a ONE.

If you believe the numerologists, ONEs have builder/initiator energy. ONEs are independent. ONEs are visionary. ONEs are courageous, decisive and inventive.

ONEs build worlds.

FIVEs like me are here to tell stories about the worlds ONEs have built, quintessence trying to stitch those worlds together.

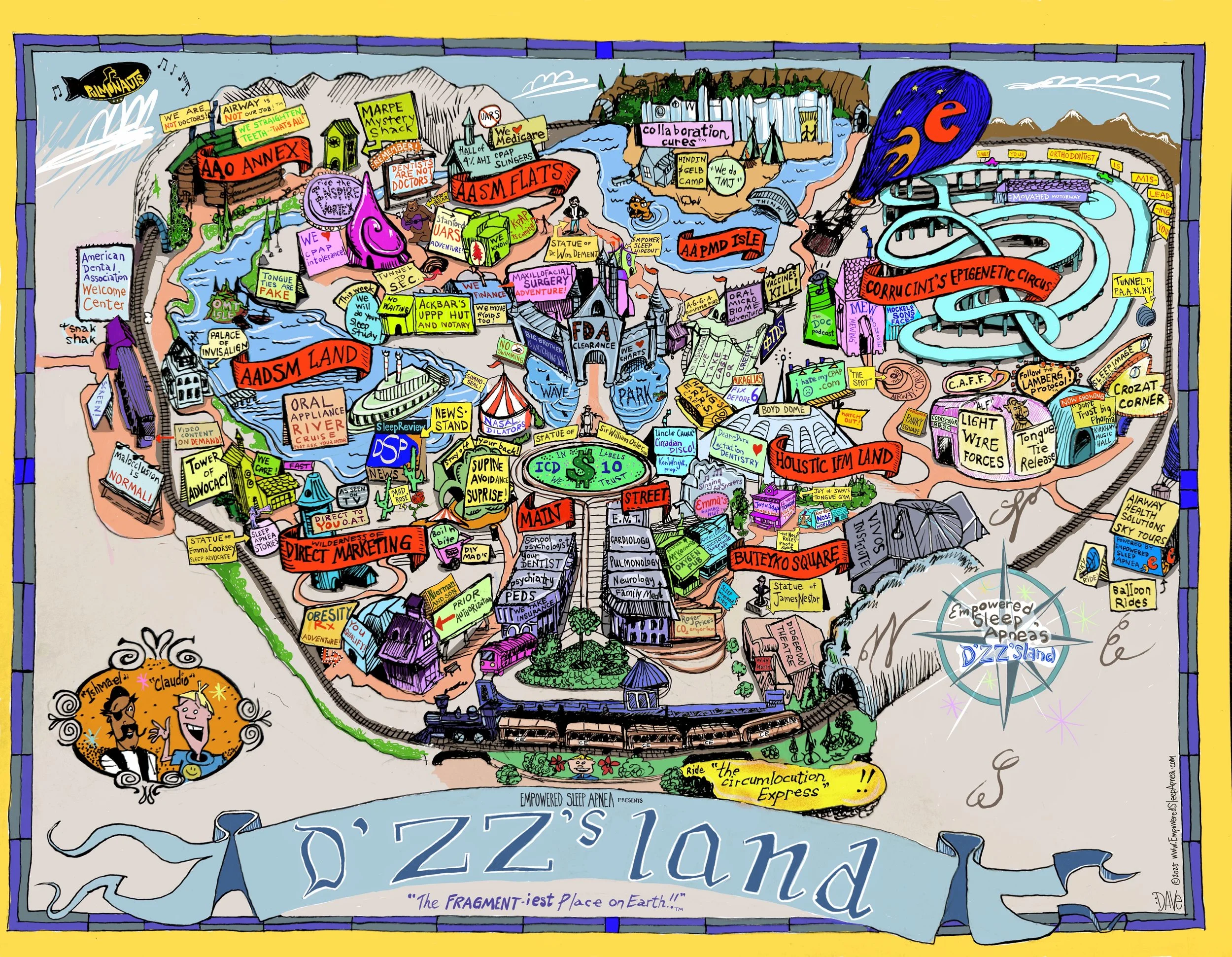

Last week, I told you the story of a persistent cartoon in my head, a bustling but ultimately disconnected Amusement Park metaphor for the curiously fragmented healthcare landscape that we all inhabit, a hideous conflagration of “rides and attractions” that was never put together by design but instead grew together spontaneously, toxically, like some sort of verrucous biology experiment gone wrong.

The Fragmentiest Place On Earth (TM)

I didn’t build this park; I’ve just worked in it. I’ve chewed on its popcorn, I’ve waited in its lines, and I’ve gawked at the coming attraction posters. I’ve explored it, inch by inch, sometimes on my hands and knees. Over the last half decade, I’ve spent time out on the causeway, interviewing folks that are caught without sunscreen or maps, in between the rides, wondering where the heck they should go next. It’s not pretty.

My final take? Walt Disney wouldn’t suffer this crap for a heartbeat. Walt Disney would shut the place down for a complete overhaul, from the ground up. Walt Disney’s park, as we’ve heard, would be clean.

So, folks, it’s here that we start—and for me, the HERE I’m visualizing isn’t Longmont, Colorado, 2025…but instead about 820 miles west and 49 years backwards.

The HERE I’m wanting to take you to is somewhere very distant from THE FRAGMENTIEST PLACE ON EARTH (TM).

…Cue backwards-music tape effects as the Blue Balloon navigates back in time…traveling Westward…Westward…Westward…

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Disneyland 1976: The Happiest Place on Earth (TM)

Disclosure: I was born and raised in Southern California, the land of beaches, movies, music and amusement parks. That much sunshine means time outside. And man, the amusement parks were everywhere!

I mean: it was serious! We had Knott’s Berry Farm, with its corkscrew rollercoaster and wild west gunfights…we had Movieland Wax Museum, with the ultra-lifelike Wizard of Oz set…we had Universal Studios tour, with the “Jaws” shark demonstration…if you wanted to drive a bit, we had Six Flags Magic Mountain, with the legendary upside-down looping coaster unveiled for America’s Bicentennial 1976 called The Revolution.

And then there was Disneyland, the Grand-Daddy of them all.

I don’t know how typical this was, but my family seemed to have a tight relationship with the Magic Kingdom. My mother’s side of the family—automotive Chatfield’s from Colorado—was crawling with Model T enthusiasts, which meant that there was a recurring gig for the Model T club to drive their chattering prizes down Main Street—a celebration of Americana, and free tickets for my family to enjoy the park when I was a baby. My parents’ best friends, Stan and Linda Primanti, met while working at Disneyland—he was a ride operator; she played Cinderella.

We had a generally assumed “rule” in our household, an understanding that a birthday equaled a trip to a park—one of our many—generally of the birthday kid’s choosing. There was a heady sense of adventure and responsibility involved in the choosing.

In September 1976, for my eighth birthday, I chose Disneyland. It’s hard, in today’s world of calculated empathic celebration and multi-zillion dollar tie-ins to fast-food chicken sandwiches, to understand just how different that place felt, back then.

The place sparkled. It was the cleanest place I’d ever seen. Everywhere you looked, there was someone in a candy-striped coat, handing a child a frozen banana or a balloon or a pirate hat. Mickey Mouse ears were everywhere.

As usual, my sister Kim and I had it all planned out. In 1976, the best rides were the immersive ones: the ones that took you all the way into the story…rides that were so good, they went ahead and made movies about them after the fact…Pirates of the Caribbean…the Haunted Mansion…Jungle Cruise. Space Mountain wouldn’t open ‘til the summer of ’77, but the rumors of a rocket-ship themed rollercoaster that operated in the darkness of space made us all wild with anticipation.

One of my favorites that year was a quirky immersion ride, the flagship imagineer’s dream in Tomorrowland called Adventure Thru Inner Space. The idea was that guests—transported by a conveyer-belt of iconic moving chairs called Omnimovers—would be shrunk in size to explore the subatomic structure of water inside a snowflake. I’m not kidding. You literally got to travel inside a water molecule, and it was just plain RAD. Narrated by the velvety baritone of veteran voice actor Paul Frees, the experience was hushed, reverential, exciting, transformative, and psychologically deep.

There was a strategy to navigating Disneyland, for those of us in the know. You got there early, before they opened the front gates. Kim and I would study the map in earnest, watching the pristine storefronts of Main Street opening up to immaculate patios, horse-drawn buggies getting geared up, train-whistles blowing, scent of popcorn and cotton candy everywhere.

There was an adventure to be had, you see, back then, planning the economy of the park itself. Back then, it was a small admission fee to get into the park, and you bought tickets to ride the rides, the tickets being valued “A” through “E”.

The “good” rides were the E-tickets, everybody knew that.

It was a thing back then. If you liked something, you’d say, “Oh, man, that’s a total E-ticket!”

Adventure Thru Inner Space was an E-ticket, and that was where we were headed first.

My point: the ticketing system created a psychology of navigating the park, where the space in between the rides was part of the adventure, and it was all safe and fun, because it was all CONNECTED.

Going in, you knew that the rides were a limited resource, so gaming the sun, the lines, the proximity to other rides, the place to get lunch, and the timing of the splashy rides were all a vital part of the calculus of field navigation. At the end of the day, tired, hot, sunburnt and satisfied, we’d watch the Main Street Electrical Parade and maybe hit up some of the A-ticket carnival rides like the Flying Dumbos or the Mad Teacups (lame!) before heading home with full hearts and happy tummies.

And somehow, the whole thing held together.

It was a thing of beauty…way different from the harried experience you’d have, riding fast, scary rollercoasters at Magic Mountain, operated by cranky college dropouts with checkerboard VANS Off-The-Walls and mullet haircuts.

So, when I got to thinking about our Fragmentiest Place on EarthTM, I got curious as to how he—meaning Disney—pulled it off. How did Walt Disney’s amusement park succeed on such a foundational level?

It turns out, the answer has something to do with INTENT.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Yeti Stori

Years ago, when my own kids were small, Em and I schlepped our nuclear family to DisneyWorld in Florida, The Happiest Place on Earth (TM), (East Coast Style). My older child was maybe seven or eight at the time, so this would have been around 2009. We had just gotten off that really RAD bobsled ride in Animal Kingdom—the one that featured a howling Yeti in the final sequence--all thrills, air-conditioned chills, and animatronics.

It was thrilling, fast, super fun…and…it scared the stuffing out of my kid.

As usual, we exited through the gift shop.

My kid was a clear standout, red-faced, frightened, in tears, in full-on meltdown mode, terror piled upon sugar piled upon jetlag. Might as well just go back to the hotel, we thought…

In Disney terms, this was a foundational problem. This was failure of mission.

Five seconds later, BAM!

A woman in a Himalayan Welcome-Wagon costume was at our side, handing a suddenly not-crying Jacqueline a small stuffed Yeti doll, all smiles and pixie-dust. No hesitation. No paperwork. No “wait here while I get my manager.”

Just: BAM! Tears gone, magic restored.

Snowball, the friendly Yeti

We could tell: that moment was no accident. That moment was the product of an entire organizational philosophy. Someone at the top had said: we will empower our staff to preserve the magic in real time. And thousands of people had been trained and trusted to do just that.

This was field-level operational empowerment in service of the show.

That, folks, has been Disneyland’s secret sauce, since the day they opened the gates to the “Magic Kingdom” in the Summer of 1955.

And as I drew the wacky cartoon of our fragmented amusement park, it got me actively wondering: How on Earth did they do it?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Four Keys: Safety, Courtesy, Show, Efficiency

Walt Disney’s vision was delight without the darkness, a clean and safe park where families could have fun together, and the whole place was a connected, immersive experience. To Walt, this came down to four fundamental principles, prioritized in order, that all employees working in the park would uphold.

Oh, and…psst!...they’re not employees anymore. They’re cast members.

Walt Disney called these four principles the FOUR KEYS, principles the company continues to teach in their corporate culture today as a prioritized order,

Safety

Courtesy

Show

Efficiency

These keys were not slogans on a wall--they were operational priorities, taught to every cast member beginning on day one in a curriculum called Traditions Training, and culturally reinforced by all levels of the hierarchy. Whether you were a boss, a ride operator, or a litter sweeper, the culture was the same.

Safety came first. Then courtesy. Then show. Then efficiency. Always in that order.

So--when my kid was melting down, the cast member’s mental model for decision-making in the field was already crystal clear:

Safety: is the child physically okay? Yes? Check! Not a seizure, just a tantrum! LOL!

Courtesy: can I show kindness right now? Yes, I can!

Show: what gesture preserves the magic? A sweet cuddly Yeti and a smile from me in my cute costume would re-frame it!

Efficiency: only then, how quickly can we get back to throughput? Temper tantrum aborted in 5 seconds, family back to spending money, powered by their own joy…

Mission failure aborted. Joy restored.

With the Four Keys, everyone in the park is working from the same script, not because they memorized lines, but because they shared the same map. Each cast member was empowered to use their own creativity, their own humanity, their own joy…to make it happen.

And this, folks, is what made the park feel whole.

And Walt Disney seemingly sucked it out of his thumb.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Enter Stanley McChrystal and Team of Teams

The thing about ONEs, they tend to pave their own way. Lillian Disney scoffed at the idea of another filthy amusement park, and Walt, the visionary showman pioneer, engineered the cleanliness into the living operation. THE PARK was a whole experience, connected by a complexity management tool called The Four Keys. True to his ONE nature, he didn’t look for a rule book for how all this should be done. He made all that up, and—wouldn’t you know it?—the process still works, the show still goes on, and people are still talking about it, to this day.

It would take almost fifty years and a person from a very different walk of life to explain why it works so well, and what we should be learning from it.

It was going to take a soldier at war.

Nearly a half-century after Disneyland opened its gates, General Stanley McChrystal would codify in his book Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World two conditions he deemed essential when addressing a complex landscape and getting people to work productively together while doing it.

McChrystal called these two conditions shared consciousness and lateral connectivity.

And Walt Disney, as it happened, nailed both of them.

Here’s the backstory: in the early 2000’s, McChrystal was commander of the Joint Special Operations Task Force in Iraq, a sort of military “Super-Friends” designed (on paper) to bring America’s most elite fighting forces together as a group…Army Delta, Air Force Special Tactics, Army Rangers, and Navy SEALs. Their mission: to subdue one of the slipperiest and most dangerous terroristic organizations on the planet… a group loosely called Al Qaida in Iraq.

Each morning, General McChrystal walked into a war room filled with the hum of dozens of monitors. Each screen showed fragments of the war—drone feeds from Fallujah, intercepted communications, logistics reports, battlefield updates. Every unit was represented, each with its own acronyms, its own jargon, its own chain of command.

It looked like control. But it wasn’t.

McChrystal realized he was fighting a networked insurgency with a machine that was built for linear warfare. His individual units were awesome, but siloed—sweet rides in Tomorrowland that did not connect to each other, efficient in their own lanes, but the lanes didn’t connect. Intelligence didn’t flow laterally. Decisions bottlenecked. By the time information got to the right people, it was too late.

Feels a lot like the Fragmentiest Place on Earth(TM)!

The Old Playbook: Command and Control

Traditional military strategy can be simplified as a “top down” management approach: the general sees (to the best of his ability) the whole playing field, orders flow downward, and units execute.

This type of “top-down” management worked OK in conventional warfare. But in Iraq, facing Al Qaeda’s decentralized, networked operatives that blended with the civilians, it was hopeless. The insurgents were more like a swarm of bees than a marching band. They adapted in real time. They shared information laterally. They didn’t wait for permission. McChrystal’s better-equipped and better-trained units were getting their butts handed to them. It was embarrassing. In our Fragmented Amusement Park, we can hear the voices of regional authorities shouting orders at crowds of patients wandering by, sometimes shouting at each other. What a hot mess!

Rising to the challenge of his complex environment, McChrystal did something radical. He tore up the old “command and control” playbook, reimagining the ways “adaptive teams” function, when they’re at their best. If his group of units had been a soccer team, he reasoned, he wouldn’t be shouting orders at David Beckham or Mia Hamm from the sidelines! He would train them to work together, using their own instincts…

Instead of clinging to control, he started sharing information with all key players. The morning briefing was no longer a handful of senior leaders; it networked hundreds of participants, connected by video. Intelligence once guarded became more widely distributed to field operatives. People who never would have been in the same room were suddenly hearing the same story at the same time.

McChrystal deemed this hive-mind mentality shared consciousness.

Then came the second step: he had to increase the adaptability of field agents to make decisions in real-time. He had to empower local units to act, by helping them bond with one another, coordinating for the shared mission amongst themselves. In other words, McChrystal was systematically allowing decentralized field-empowered decision-making.

Under this new paradigm, a Navy SEAL team in Mosul wouldn’t need to radio headquarters for permission to coordinate with an intelligence cell in Baghdad. In the soccer-team scenario, an upfield player kicks the ball downfield because she knows her teammate is fast enough to be there, and the two share a vision as to where the ball is headed. In either event, the decision is made organically, in real time, because teammates learned to trust one another, and they could predict one another’s actions.

McChrystal called this field-empowered, decentralized decision-making lateral connectivity, and he has since proclaimed that this element was foundational to their cultural shift.

Imagining it is one thing…making it happen is something else. McChrystal realized quickly that he couldn’t get teams to connect by ordering them to get along. Each group had internal morale that was decades old, protected by solid steel ego-armor, with an internal mantra: “EVERYONE ELSE SUCKS!”. Getting them to work together was not obtainable with a command, at least, not directly. McChrystal needed a new plan, something utterly unconventional. A new plan to make fighting teams play nice with one another.

He accomplished this challenging feat of social engineering by grace, not by force…by cross-pollinating teams, embedding, say, a SEAL with Delta Force for a spell, all the while encouraging each team to send their best “diplomat” to the other side. The purpose was explicitly competitive in its goal for collaboration—to establish humane connections between teams by promoting a common culture.

And you know what? It totally worked!

The effect was transformative. The machine became a living network. The war didn’t get simpler—it stayed brutally complex—but the organization could now adapt at the speed of complexity.

McChrystal’s lens helps us understand Disney’s intuitive success—Traditions Training ensured a shared vision of the complexity of the mission—east cast member with the goal to create happiness!—while the Four Keys complexity deconstruction tool allowed for decentralized & adaptive field-empowered decision-making, i.e.: lateral connectivity.

All of this got me thinking…maybe it gets you thinking too, Life-Fans! After all, when it comes to ground rules, don’t we already have something similar to the Four Keys? Don’t we already have a rule book, for how the game should be played?

Maybe it’s time we talked about the Principles of Medical Ethics?

After all, if there are some rules to be agreed upon in The Fragmentiest Place on Earth(TM), maybe this is a good place to start?

The music swells as the lights dim and the stage show rotates to the next scene…going back in time…back to the days of Hippocrates…

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

History of Medical Ethics: A Condensed Version

People are fond of quoting the Hippocratic Oath—primum non nocere—literally translating to “first, do no harm.” The meandering history of “medical ethics” is deeper, more troubling, and ultimately more humane than this famous--and arguably low--bar.

So, let’s take a tour!

From antiquity to the early modern period, ethics in medicine was about your character more than anything else. In other words, the focus was on who you were, rather than how you reasoned.

Hippocrates (5th Century BCE) established ideals about non-malificence, confidentiality, and loyalty to patients, but always from the physician’s perspective. Moral excellence was seen as a personal trait: prudence, compassion, and temperance were virtues that defined a “good doctor.” You learned about these traits by apprenticeship… young physicians learned ethics by watching a respected mentor behave nobly. This was virtue ethics in practice…Aristotelian in flavor, embodied, relational, and local.

Later, in medieval and early modern Europe, moral reflection in medicine became intertwined with theology and duty to God. Ethical instruction was about aligning medical duty with divine law and charity…” healing” was seen as an extension of Christian compassion, while suffering, on the other hand, had moral meaning. Ethics in this age emphasized duties to patients, colleagues and society—a gentleman’s code of honor, rather than a pluralistic moral system.

By the mid 19th century, we begin to see modernization of medical training in Europe and the U.S.A., and medical ethics began to take on a decidedly “top down” management flavor, emphasizing benevolence, confidentiality, non-abandonment, and the role of the physician as paternal guardian. Patients, in return, owed obedience, gratitude and truthfulness. This timeframe also saw a strict turn in etiquette for physicians’ duties to each other and the profession at large.

During this timeframe, we see a strict hierarchy emerge, vestiges of which are still present today. We see indignance and moral condemnation for colleagues who criticize fellow physicians, for those uncouth enough to advertise their services, and for those unclean enough to fraternize with “irregular” providers, such as homeopaths, midwives, and empirics. The “guild” of medicine thusly born in a flurry of cultural moralizings, the intellectual stone-throwing begins!

The paternalistic tone of medicine received a cultural haymaker to the jaw with the Nazi atrocities of WWII, bringing about the Nuremberg Code of 1947 and (eventually) the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964. The 1960s brought the American ethical disasters of Tuskeegee and Willowbrook, where privileged men in white coats intentionally gave syphilis to black prisoners and hepatitis to intellectually disabled kids (all in the name of science).

And let’s not forget about the armies of children hideously deformed from the “harmless” drug Thalidomide that was used to manage pregnancy-related nausea, or the men in white coats who told us that smoking was harmless, or… or… or...

For doctors, by the 1970’s, the optics on ethical behavior were really, really bad.

Medical ethics needed a reform.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Enter: Beauchamp & Childress, 1979

(Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (1979). Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press).

Drawing on classical humanistic philosophy, collaborative philosophers Beauchamp & Childress created a framework that allowed for pragmatic discourse on four medical ethical principles, allowing for deeper ethical discussions that would arguably prevent disasters like Willowbrook from ever happening again.

From Immanual Kant, they took respect for individual persons (autonomy). From John Stewart Mill, they took utilitarian concern for welfare (benificence). From Hippocrates, they continued the command to avoid harm (non-malificence). And from the American visionary of jurisprudence John Rawls, the principle of fairness (justice).

Under the new system, medical ethics was emancipated from the “what kind of person are you?” guild system, stepping into a more pragmatic era, one that’s supposedly centered on the patient’s experience.

All of this brings me to why I’m paying attention to what’s going on, out there, between the rides of our Fragmented Amusement Park. In the first essay of this series, we explored the notion that divergence of language in various parts of the park causes massive systemic suffering, with the emergence of regional differences in the answers to three foundational questions that we must navigate every day:

1. WHAT IS SLEEP APNEA?

2. WHY SHOULD IT BE TREATED?

3. WHAT ELSE COULD IT BE?

Unlike Disney’s park, where cast members in different “lands” agree on mission-critical responses to key questions, our park is likely to give us “regionally appropriate” answers but leave us unprepared for a park-wide exploration.

What’s needed is a zoom-out. What’s needed is a change of perspective. What’s needed is a Blue Balloon that’s high enough for us to get a gander at the whole park and start asking questions about what’s missing.

See, if we press our Principles of Medical Ethics up against Disney’s Four Keys, we start to see a pattern of ethical violation, coming from the setup of our Fragmented Park itself.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Mapping Disney’s FOUR KEYS to Medical Ethics

Walk with me, here.

If we can accept the metaphor that our healthcare system is a fragmented amusement park…and we accept that Walt Disney slam-dunked the “connected” amusement park concept with his Four Keys…my question is what happens when we view our precious Principles of Medical Ethics from Disney’s lens. It leads one to ask: Where is our current system failing?, and what can this thought experiment potentially teach us about a pathway forward?

The Four Keys, Revisited--Amongst Disney’s four keys, “Safety” was key number one. As I pondered our current Fragmented System, I had a nagging feeling Walt wouldn’t be happy about how this Key is doing, overall.

Let’s think about what makes a patient feel safe in a medical environment--it’s a complex question! After all: feeling safe is a FEELING! When safety is violated, it can be an emotional sensation, in addition to a physical one! In medicine, safety is existential.

We can see that in medical situations, “safety” is arguably written into all four of our ethical principles!

To wit: it makes us feel SAFE to believe that our provider is looking out for our best interest (beneficence). We also want to believe they’re not recommending something harmful just because it’ll be paid for, and they’ve got a boat payment to make (non-maleficence). We want to know that our personal opinions matter, so we want the facts about our condition before we make decisions (autonomy). We want to know that our provider isn’t discriminating based on our payer class, and we don’t want to have to wait forever for care (justice).

In other words, when we think about it, all Four of our Medical Ethical Principles map to Disney’s first key.

And we’re just getting started!

Just for fun, let’s take another look at what happens when our ol’ pal Claudio bounces off several different versions of our first foundational question-- “WHAT IS SLEEP APNEA?”--it’s easy to see how the divergence of language violates his sense of safety!

A simple question…

The hilarious part is that nobody seems to recognize it’s even happening, so nobody does anything about it! Hilarious!

Fun game, huh?

Turns out, we can map each of Disney’s Keys to one or more principles of Medical Ethics!

COURTESY is Autonomy and Beneficence made visible. Every act of humanizing respect tells a person, “You belong here” and “we are looking out for you.” When clinicians use shared language, co-author decisions, and listen without hierarchy, they transform courtesy into freedom.

SHOW is Beneficence that’s choreographed to emphasize our patient’s humanity, the design of caring so that personal Autonomy is a felt part of the process.

The EFFICIENCY Key maps to the medical ethical principle of Justice. It’s the moral engineering of flow—ensuring access, reducing wait times and waste, and distributing time and attention fairly. When systems run smoothly for everyone, fairness becomes embodied.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Way Forward

The solution to a problem requires a different mindset than the problem itself, or so we’ve been told.

In this series, we’ve seen the devastation of the Fragmentiest Place On Earth(TM)—heck, we live it, every day! Now, we’ve had the nostalgic chance to remember what it was like when it was done right—revisiting Disneyland 1976--and we’ve learnt about the Four Keys “secret sauce” behind that continuing intuitive success.

We learned from General Stan McChrystal’s Team of Teams project why Disney was so successful—he created an environment that fostered a shared consciousness of the complexity of his mission using Traditions Training, and he empowered his field operatives to make mission-appropriate decisions with the Four Keys complexity deconstruction tool (lateral connectivity with distributed decision-making).

We’ve taken it one step further to see how these Four Keys allow a different lens into the WHY behind our Four Principles of Medical Ethics, allowing some speculation on what Walt might think about our current Fragmented Park.

In reviewing this journey, in all of this, I’m reminded about the stunning importance of INTENT, because this is where all of this mess is heading.

It’s a meditation on where we should we go.

Indeed, INTENT is everything.

There’s a saying that I’ve picked up since I’ve moved to Colorado, an aphorism from our back country skiers, arguably folks who know a little something about navigating complexity. It’s a saying about the LENS we carry and what we choose to see.

It’s a saying about INTENT, and I think it’s a good one to close with. As usual, it feels better with a cartoon…

Ski the path, not the trees.

With that, Life-Fans, I’ll leave you until next time with the question that’s the title of this series:

“What would Walt Disney Do?”

That’s the question I’m lobbing skyward as we collectively think about our pathway forward, and I’ll leave it with you with a kind farewell, until next week…

…that’s when I’ll come back with my answer!

…I’m hoping it’ll be an “E-ticket!”

Kind mojo,

Dave

David E McCarty, MD FAASM

Longmont Colorado

4 November 2025

David E McCarty MD FAASM is the Chief Medical Officer of Rebis Health and the co-creator (with Ellen Stothard PhD) of the Empowered Sleep Apnea project. He will return next week with the third and final installment of this series “What Would Walt Disney Do?”

Though Dave is a fan of Walt Disney and Disneyland, he is not a paid endorsee of Disney, Inc.