To Cover?…or Not to Cover?…That is the Question

OR: The Ethics of Defining “Sleep Apnea” in an Age of Coverage, Codes, and Conscience

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

By David E McCarty MD FAASM (…but you can call me Dave)

29 December 2025

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“The good physician treats the disease…

…the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

--Sir William Osler

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A humane question deserves a humane answer…

There’s a moment in the encounter when the room goes quiet.

The Home Sleep Apnea Test is back; the numbers are on the page; the patient is waiting.

Somewhere between the Apnea Hypopnea Index and the insurance portal, a question hovers in the air, like the aroma of a five-day-old Filet-O’Fish sandwich on a hot summer’s day…

What exactly is this problem anyway?...and who gets to decide?

“Sleep Apnea”, for all our cross-siloed technological sophistication, decades of research, and field-level engineering innovation, still rests upon language, which is to say: how we talk about this problem affects the journey!

What counts as disease? How do we talk about risk?

What are the meaningful details that determine whether treatment is necessary?

Let’s pass the conch around the room whilst everyone has a chance to speak their mind—I’ll bet we’ll see some red faces and some clenched fists! So much diversity of opinions! My English-Major brain is having a field day! What fun there is to be had with language!

I call attention to this kerfuffle for a point. You see, your honor, the game doesn’t stop here…as a follow up question… if we believe that treatment is somehow necessary, shouldn’t it be…um…covered?

GASP!

Cue record-scratching sound effect as the whole party stops, and everyone is staring directly at you.

Aye, there’s the rub!

That last word [COVERED] has quietly become one of the most ethically powerful forces on the modern Sleep Medicine landscape. It shapes access, narrows clinical imagination, and increasingly substitutes administrative clarity for physiological understanding.

This essay is an attempt to examine that power through the lens of the Four Principles of Medical Ethics:

JUSTICE, AUTONOMY, BENIFICENCE, and NON-MALIFICENCE

…so that we may ask whether our current definitional ecosystem still serves the people it was meant to help.

To begin with, let’s take a moment and talk about the concept of DEFINING a DISEASE…

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Definitions Are Never Neutral

In medicine, diagnostic criteria are often presented as technical achievements that are carefully negotiated, evidence-based, and refined over time. The nagging problem is that these definitions are never merely descriptive, they’re operational. They can open (or close) doors!

They create categories of belonging and exclusion.

Silos, in other words.

In Sleep Medicine, the dominant clinical definition of obstructive sleep apnea has been stewarded by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), an organization that has acknowledged the evolving nature of Sleep Apnea over time, albeit cautiously. Over the last two decades, the definition of Obstructive Sleep Apnea (ICD-10 G47.33) has evolved, recognizing that non-desaturating events are potentially clinically meaningful, accordingly adjusting the definition of “hypopnea,” and allowing greater lateral reach for symptom requirements. The message (at least in spirit) has been pretty clear. If the AASM as an organization could speak about this issue, it might say something like:

“Ahem…thank you for the opportunity…our understanding of sleep-disordered breathing is incomplete…and humility is a required asset in our continuing discovery of this complex problem. Thanks for the opportunity. Oh, and COME TO THE MEETING!”

In other words: shout out where shout out is due! The AASM’s definition has shown adaptive capacity! That’s worth crowing about! CAW! CAW!

However…

Running parallel to this living clinical language, there stands a far more rigid structure: coverage criteria, particularly those established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). These criteria, necessarily designed for scale, auditability, and fraud prevention, convert complex physiology into binary gates.

“Covered” or “not covered”.

Eligible or ineligible.

Treated or untreated.

Life-Fans, the ethical tension arises when the language of these two systems diverge.

That’s when the fireworks start.

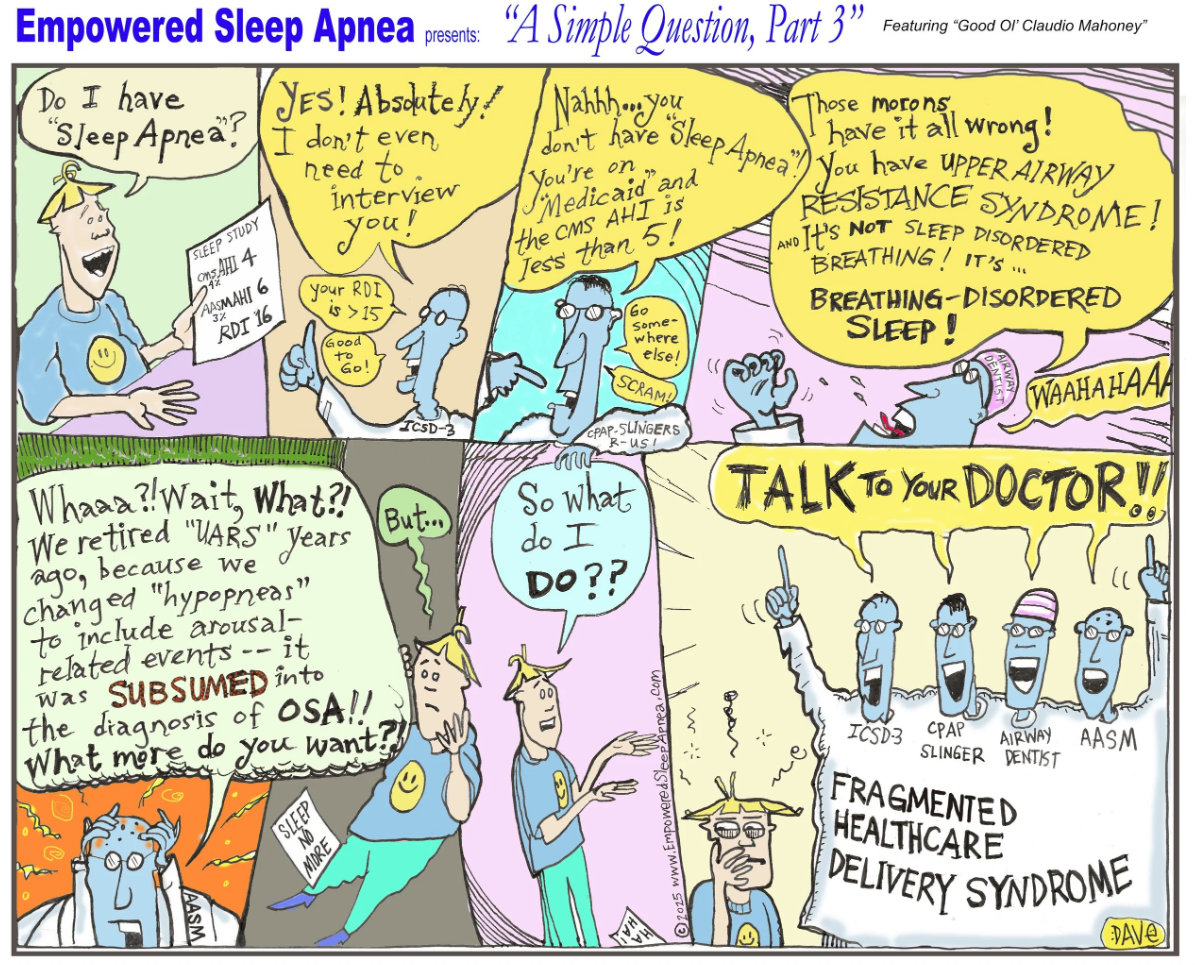

A Simple Question: PART 3. McCarty, David. “A Simple Question Part 3.” Sleep Review (Nov/Dec 2025 print issue), Sleep Review Magazine, MEDQOR LLC. November/December 2025. This cartoon originally appeared in Dave’s Notes 1 June 2025 accompanying an essay entitled A Simple Question and the Hydra of Diagnosis.

A Brief Detour: Why Medical Ethics Exist at All

As I reviewed in a recent essay, the four familiar pillars of medical ethics—justice, autonomy, beneficence, and non-maleficence—did not arise because medicine was doing well. They arose because medicine, when unexamined, has repeatedly caused harm.

Justice emerged from inequity and rationing. Autonomy from paternalism and abuse of authority. Beneficence and non-maleficence from the hard-earned realization that intervention is not synonymous with healing.

These principles were never meant to live in textbooks, to be admired by academicians in frock hats. They exist precisely for moments like this one: a time when the system has grown too large, when efficiency incentives multiply, when individual patients risk the harm of being labelled, processed, and left behind when a “one size fits all” solution fails.

I’m writing this essay because Sleep Medicine has reached this moment.

To be fair (and this matters) the AASM’s clinical posture has generally reflected ethical humility. The organization has acknowledged that the beast we all go around calling “Sleep Apnea” is not a monolith, that its manifestations vary across age, sex, comorbidities, and physiology, and that no single metric fully captures its impact.

This approach aligns naturally with beneficence: responding to real human harm rather than rigid thresholds. It also preserves autonomy, allowing clinicians and patients to interpret findings together in context. And it reflects a tacit commitment to non-maleficence by resisting the urge to declare certainty where uncertainty persists.

But, back to the rub, Horatio: clinical definitions, however thoughtful, do not control access to care.

Excuse me, as I light the fuse to this bottle rocket…the fireworks show is starting!

CMS: Definition as Gatekeeper

CMS definitions were never written to describe all aspects of a disease; they are procedural document that allows determination of payment. This is not a moral failure, just a recognition of purpose. We’re dealing with an administrative necessity within a system responsible for millions of beneficiaries. In other words, this is not a sensemaking tool for determining the “why” of therapy. This is a gargantuan vending machine of delivery, a massive exercise in “how”.

The ethical problem arises when definitions designed for payment become mistaken for definitions of disease. When an AHI cutoff determines not only whether therapy is reimbursed, but whether the condition itself is treated as “real,” justice subtly shifts from relational fairness to procedural compliance. Autonomy erodes, as patients learn that their lived experience carries less weight than a decimal point. Beneficence becomes conditional, activated only when eligibility criteria are met.

And non-maleficence? It becomes oddly inverted: harm is tolerated not because treatment is dangerous, but because it is uncovered.

Justice at the Fault Line

The medical ethical principle of JUSTICE asks simple questions: Who benefits, who bears the cost and is this FAIR?

Under rigid coverage criteria, certain populations predictably fall through the cracks: patients with milder indices but severe symptoms, women with arousal-predominant disease, patients with comorbid insomnia or cardiopulmonary vulnerability that does not neatly inflate the AHI.

Let’s also not forget that CMS oversees medical coverage for those who are financially vulnerable, which is to say senior citizens and those with means too limited to afford private insurance. When we systematically devalue these individuals, we no longer shine with the bright light of JUSTICE.

At the same time, others may be pressured into treatment that technically satisfies coverage definitions but fails to meaningfully improve their sleep, their days, or their lives. We can see that JUSTICE, in this context, is not only about access—it is about appropriateness.

A system that over-treats some while excluding others is not merely inefficient. It is ethically distorted.

Autonomy in a Checkbox World

Autonomy is often misunderstood as “having a choice” but it’s bigger than that. In reality, it requires meaningful participation, which is to say that our patients have the ability to understand, weigh, and co-author decisions about their care, a process that pioneering person-centered dentist Dr. Bob Barkley called “co-discovery.”

“Co-Discovery”—A magnificent word! Thank you to Dr. Paul Henny (author of CoDiscovery: Exploring the Legacy of Robert F Barkley, DDS) for teaching it to me, and for giving this insightful and powerful word the airtime it duly deserves!

On the other hand, when coverage criteria ossifies, autonomy collapses into compliance. Conversations narrow. Shared decision-making becomes performative. Patients learn, quickly, which stories “count.”

The ethical injury here is subtle but real: patients are not denied a voice outright; they are taught that their voice has limited jurisdiction, and that they might need to “shop around” to find someone who’ll actually listen to them.

Beneficence, Non-Maleficence, and the Metrics Mirage

Sleep Medicine now sits at the intersection of expanding technology, remote monitoring, and increasingly granular data. The groundswell of interest in all things SLEEP illustrates the extraordinary opportunity here, and anyone paying attention to the field can feel it. Home monitoring and artificial intelligence are conspiring into a perfect storm of diagnostic deluge.

With this tidal wave of case-identification coming, I’ll make the controversial claim that the time for AWARENESS-CAMPAIGNING is over. Indeed, instead the time has come for us to reckon with the imminent arrival of massive amounts of biological data, along with the busloads of worried patients attached to them. See, when success is defined primarily by device-generated metrics rather than patient-centered outcomes, beneficence can quietly mutate into optimization for its own sake. Non-maleficence, meanwhile, is rarely violated dramatically—but often violated invisibly, through over-titration, over-labeling, and the erosion of trust.

“Does this reduce the AHI?” is simply not enough…the ethical question stinking up the room fish-sandwich-style:

“Does this intervention help the human being in front of us heal?”

Enter: DENTISTRY

Into this already complex landscape steps dentistry, bringing with it structural models, preventive instincts, and, notably, relative independence from CMS coverage constraints.

This is neither good nor bad by default, but it is ethically consequential.

When upstream definitions remain rigid while downstream interpretations diversify, field engineers devise interesting solutions, and parallel truths emerge.

One unintended consequence of rigid coverage criteria is not simply exclusion, but migration. Patients unsatisfied by the limitations of a CMS-defined practice will seek a more nuanced understanding.

Remember: it’s not a magic act! When patients get “left behind” by a CPAP-focused system speaking in thresholds and compliance metrics, they do not just “disappear.” Instead, they go looking for someone who will listen more carefully to their story.

Increasingly, that “someone” is an Airway-Focused Dentist—often a clinician with a more sophisticated understanding of nasal breathing, non-desaturating respiratory events, and functional/structural contributors to sleep disruption. For many patients, this encounter feels more humane, more attentive, and more aligned with their lived experience of sleep.

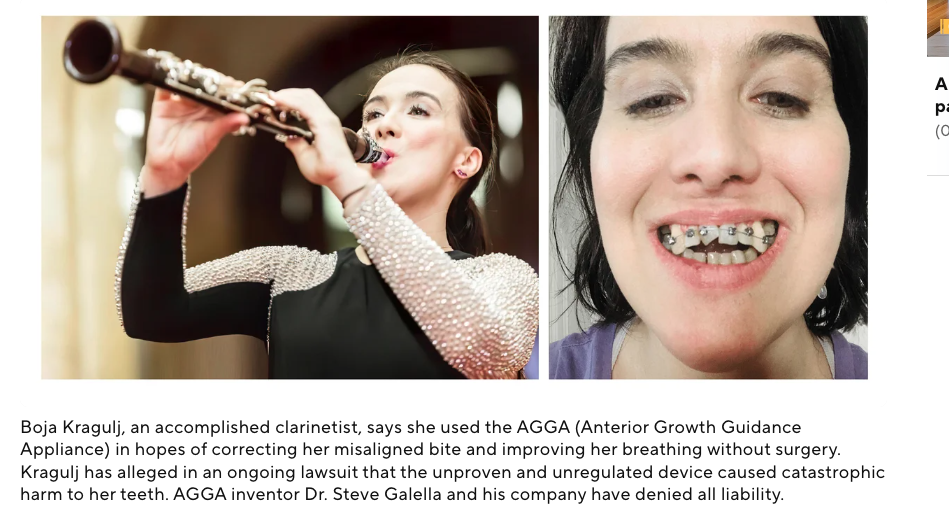

But here, too, an ethical risk quietly emerges.

When care is organized around labels rather than longitudinal goals—you have “Sleep Apnea”, therefore I must treat you—even the most well-intentioned clinician can drift toward a one-size-fits-all solution. In dentistry, this can take the form of over-titration: an escalating structural intervention driven less by unfolding patient benefit than by confidence in the intervention itself.

This is not a failure of goodwill or intelligence. It is a failure of structural humility.

Without an explicit framework that continually asks why we are treating, what we are trying to improve, and how we will know if we are helping rather than merely intervening, any discipline—medical or dental—is vulnerable to mistaking action for beneficence. The risk is not unique to dentistry. It is endemic to systems that lack a shared language for complexity.

This is precisely where multidimensional frameworks—such as the Five Finger Approach and the Five Reasons to Treat—serve not as dogma, but as ethical guardrails. They slow us down. They force re-orientation toward patient-centered outcomes.

They remind us that belief in a tool, however powerful, is never a substitute for ongoing epistemic humility, and a patient-centered approach.

When Advocacy Becomes Moral Evidence

It is not accidental that patient advocates have begun pressing this issue directly in Washington. Organizations such as Project Sleep, under the leadership of Julie Flygare, JD, have taken concerns about outdated sleep apnea coverage criteria to policymakers—arguing that rigid definitions are limiting access to care in ways that no longer reflect contemporary science or patient experience.

This advocacy matters because it demonstrates something essential: the definitional gap has become a lived ethical problem. When patients and advocates must appeal to Congress to reconcile clinical reality with coverage policy, the system is signaling distress.

Life-Fans, the point here is that the medical ethical principle of Justice isn’t a theoretical discussion…and patient Autonomy is no longer an egg-headed abstraction.

The ethics of definition have entered the public square and it’s all happening RIGHT NOW.

Definitions Should Serve Healing

None of this is an argument for abandoning standards, nor for replacing structure with sentiment. It is an argument for remembering why definitions exist at all.

They are not ends. They are instruments.Precision medicine without ethical clarity is just sharper fragmentation. Metrics without meaning are noise. “Coverage Critera” without a conscience is just rationing by another name.

If Sleep Medicine is to mature in our new era of wearables, dentistry, remote monitoring, and expanding access, it must treat definitions not as weapons or shields, but as shared language in service of healing.

See, folks, at the end of the day, it’s not a question of TO COVER or NOT TO COVER, it’s a question of whether, in our pursuit of efficiency and clarity, we can collectively remember what we are supposed to be here for, in the first place.

As for me, I’m envisioning language and a system that supports healing of the person, not one that simply labels and intervenes upon their disease.

In short, I guess you could say I’m with Dr. Osler.

Kind mojo,

Dave

PS: Empowerment Saves!

David E McCarty MD FAASM

Longmont Colorado

29 December 2025

David E McCarty is the co-creator (with Ellen Stothard, PhD) of the Empowered Sleep Apnea project and is the Chief Medical Officer at Rebis Health.

References/Further Exploration:

McCarty DE. Beyond Ockham's razor: redefining problem-solving in clinical sleep medicine using a "five-finger" approach. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010 Jun 15;6(3):292-6. PMID: 20572425; PMCID: PMC2883043.

Werner, Anna & Kelman, Brett. This dental device was sold to fix patients’ jaws. Lawsuits claim it wrecked their teeth. CBS News, March 2, 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/agga-dental-device-lawsuits-teeth-damage

U.S. House of Representatives – Office of Rep. Juan Ciscomani. Rep. Ciscomani Leads Bipartisan Letter Urging CMS to Modernize Sleep Apnea Coverage Standards. Press release, December 17, 2025. https://ciscomani.house.gov/media/press-releases/rep-ciscomani-leads-bipartisan-letter-urging-cms-modernize-sleep-apnea?utm_

McCormick, Thomas R., D.Min. “Principles of Bioethics.” University of Washington Department of Bioethics & Humanities. Accessed 2025. https://depts.washington.edu/bhdept/ethics-medicine/bioethics-topics/articles/principles-bioethics. This article explains that Tom Beauchamp and James Childress first published Principles of Biomedical Ethics in 1979, popularizing the four-principle approach (respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice).

Henny, Paul A. CoDiscovery: Exploring the Legacy of Robert F. Barkley, DDS. Codiscovery Press, August 25, 2023. ISBN 979-8988896012. Paul A. Henny’s CoDiscovery: Exploring the Legacy of Robert F. Barkley, DDS explores the origins and purpose of the “CoDiscovery” concept in relationship-based, health-centered dentistry and its relevance for contemporary practice