When Childhood Traits Become Adult Bodies

OR: ADHD, Breathing, and the Long Arc of Physiology

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

by, Kevin Boyd, DDS, MSC

&

David E. McCarty, MD, FAASM

(but you can call me Dave)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

26 January 2026

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“The universe is wider than our views of it.”

--Henry David Thoreau, Walden

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

FRONTISPIECE: The paper that caught our eye…Stott J et al. JAMA Network Open. 2026;9(1) [1]

When Early Neurodevelopment Leaves a Long Physiologic Shadow

A new longitudinal paper out of the UK¹ caught our eye recently—partially because it repeated something that may be called “radical,” but mostly because it said something that many of us have been sniffing at for years. ADHD traits in our young may be telling us something about physiologic strain long before disease ever appears.

The study followed a large, representative birth cohort for more than four decades and asked a deceptively simple question: Could traits associated with ADHD in childhood persist as physical illnesses into adulthood? The answer, statistically speaking, was *YES*—modestly, consistently, and in ways that did not disappear after adjusting for social class, sex, and other familiar confounders.

Children with higher ADHD behavioral and inattention traits at age 10 were more likely, by their mid-40s, to carry a greater burden of physical illness and physical-health–related disabilities, such as diabetes, cancer, asthma, migraines, and other illnesses. Some of that risk flowed through familiar pathways—smoking, higher body weight, psychological distress. Some of it did not fully resolve even after those factors were accounted for.

We think it’s important to understand that this was not a paper about diagnosis. Most of these children were never “labeled” as “having” ADHD. Moreover, this was not a paper about blame. The effect sizes were small, and the authors were careful to emphasize heterogeneity and resilience of many individuals. To wit: many people with ADHD traits live long, healthy lives.

And yet…

What this paper really describes is not ADHD as a disorder, but neurodevelopmental vulnerability as a life-course condition—one that can slowly shape how a body meets the world over decades.

We think that this framing matters. As Thoreau reminded us long ago, “the universe is wider than our views of it”—and sometimes what needs to change first is not the data, but the lens through which we interpret it.

See, we’ve found that once you start thinking in life-course terms, a different set of questions comes into view.

It’s not: Does ADHD cause disease? But instead: What happens when a nervous system that struggles with dysregulation, inattention, and hyperarousal has to navigate modern life for forty or fifty years?

And perhaps more importantly for us at Rebis:

What are the modifiable physiological threads in that long story?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

What the Paper Says—and Doesn’t Say

Let’s start with this: as sleep/airway nerds, we feel it’s important to be precise!

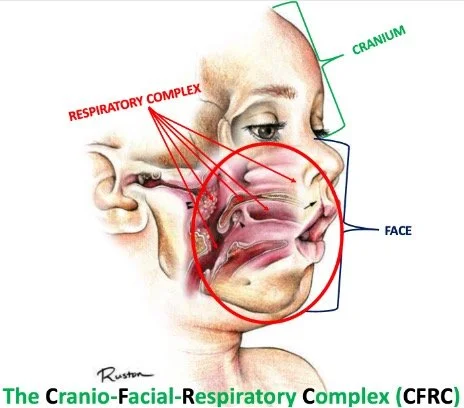

This UK cohort study did not measure sleep, breathing, airway anatomy, inflammation, oxidative stress, or markers of long-term sympathetic overdrive. To our specific interests, this investigation did not directly examine or discuss any specific biological systems known to be involved in the balance of sleep and respiration, such as the cycling of sleep stages, the functioning of the glymphatic system, or the structural-functional optimization of the bony and soft-tissue constituents of the functional upper airway, the so-called craniofacial respiratory complex (CFRC) (Fig. 1).

We at Rebis have clinically embraced the narrative that breathing and sleep are foundational components for optimal growth, development, and health.

So: let’s just say this paper interests us. A lot.

Figure 1: The Craniofacial Respiratory Complex (CFRC)—there’s a lot goin’ on there!

Having said that, we admit that saying “this paper proves ADHD is caused by breathing problems” would be a reach.

But the paper does tell us something useful and increasingly hard to ignore: early neurodevelopmental traits can translate into adult physical illness through cumulative, embodied pathways, many of which are modifiable.

Smoking is modifiable. Body weight is modifiable. Psychological distress is modifiable. The paper assumes we all know this.

The CFRC is modifiable…

See, from a sleep-medicine and autonomic-physiology perspective, all of these variables are deeply entangled with sleep quality, stress regulation, and breathing physiology. That relationship is well established across multiple disciplines, even if this particular paper did not measure those mechanisms directly.

This is not proof, of course.

But good science is also about recognizing a pattern worth paying attention to.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A Broader Life-Course Signal: Self-Control, Aging, and Healthspan

Importantly, this UK ADHD-trait paper does not stand alone.

A landmark longitudinal study from the Dunedin birth cohort followed children from birth into midlife and examined childhood self-control—a construct that overlaps substantially with attention regulation, impulse control, and executive function.² The findings were striking.

Lower childhood self-control predicted:

Faster biological pace of aging

More advanced facial aging

Worse physical health and chronic disease morbidity by midlife

More criminal behaviors and addictive substance abuse

Poorer wealth management

Lower general preparedness for aging

These associations persisted even after controlling for childhood IQ and socioeconomic status.

Perhaps most importantly, the authors emphasized that self-control is not destiny. Change remained possible in adulthood, and midlife emerged as another meaningful intervention window.

Together, these studies point toward a shared life-course signal: early challenges in regulation—however they are labeled—can shape the pace at which bodies age.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Enter Airway and Malocclusion

In each of the health disciplines of Dentistry and Sleep Medicine, we are finally learning to collaboratively explore malocclusion (suboptimal CFRC structure and function) not merely as a cosmetic or orthodontic problem, but as a developmental footprint—a physical record of how mastication/chewing, breathing, posture, neuromuscular tone, and growth has interacted over ontogenetic (birth to death) and phylogenetic (evolutionary) time.[3]

When growth/development of the CFRC is constrained, we often see:

a narrow maxilla and limited nasal airspace

a retruded mandible with a posteriorly positioned tongue

dental crowding, sometimes managed by extractions to “make room”

These are not just alignment issues. They are spatial and functional compromises.

At the same time, a growing body of work suggests that chronic mouth breathing, sleep fragmentation, and subtle airway obstruction in childhood can influence attention, behavior, and emotional regulation—not as a single cause, but as part of a “many-moving-parts” [4] system.

From that perspective, it becomes reasonable—not proven, but reasonable—to wonder whether some children described as “hyperactive” or “inattentive” were also children whose nervous systems rarely found sustained rest.

If sleep is fragmented early and often enough, the developing brain adapts; if breathing is inefficient enough, the body compensates.

See, it’s like this: adaptation works—until it doesn’t.

Decades later, the bill we owe may come due not as ADHD, but as hypertension, metabolic disease, chronic pain, disability, or shortened healthspan.

The UK cohort paper does not name breathing, though it describes a destination that sleep and breathing plausibly help shape.

Given that we all breathe and we all sleep, this should interest all of us.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

From Midlife Morbidity to Lifespan—and Brain Health

The implications of this study extend beyond midlife illness.

A recent UK matched-cohort study using primary care mortality data found that adults with diagnosed ADHD live significantly shorter lives than the general population—approximately 7 years fewer for men and 9 years fewer for women.[5] The authors were explicit: this reduction in life expectancy is unlikely to be caused by ADHD itself, and is more plausibly driven by modifiable risk factors and unmet health-care needs.

This is a sobering finding.

It also reframes the conversation away from diagnostic labels and toward systems of support, physiology, and prevention.

Against this backdrop, the 2024 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention[6] is especially interesting.

The Commission appropriately identifies oral health as a modifiable risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline. Notably, however, it does not explicitly address craniofacial development, malocclusion, sleep-disordered breathing, or airway anatomy.

Importantly, existing evidence linking late-life dental or periodontal disease to dementia remains inconsistent, with substantial confounding by socioeconomic status, education, and comorbidity, and with most studies limited to short follow-up in older adults [6]. This uncertainty reinforces—not weakens—the case for exploring earlier, upstream developmental pathways rather than focusing solely on end-stage dental disease.

These observations are offered not as criticism, but as context.

Given what we now understand about sleep disruption, intermittent hypoxia, inflammation, and neurodegeneration, craniofacial and airway development may represent an underexplored—but biologically plausible—link between early-life neurodevelopment and late-life brain health.

That hypothesis deserves study.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Lure of Oversimplification

There is a temptation—especially when worlds collide—to collapse complexity into a single explanatory story:

“ADHD is really just airway disease.”

That story is neat; it is also wrong.

ADHD is heterogeneous. Airways are heterogeneous. Lives are heterogeneous.

Our job is not to replace one reductionism with another.

Instead, these converging data invite contextual thinking: ADHD traits and self-regulation challenges may signal a body that has had to work harder, regulate harder, and adapt harder over time. Breathing and sleep dysregulation—being biologically foundational—may be important contributors in some individuals, and less relevant in others.

Seeing that clearly allows navigation without blame.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Why This Matters for Rebis

At Rebis, we are not trying to retrofit childhood labels onto adults. We are trying to help people understand why their bodies ended up where they are—and what levers remain available.

The value of these papers is not that they tell us what to do tomorrow morning. It is that they support a life-course lens in which:

early neurodevelopmental traits matter,

cumulative physiological stress matters, and

modifiable pathways still exist—not only in childhood, but well into midlife.

Breathing matters because it sits at the intersection of sleep, autonomic tone, stress physiology, and behavior. Dentistry matters because it leaves visible evidence of developmental adaptation. Narrative matters because people need a way to hold complexity without shame.

The goal is not to point fingers. The goal is to restore agency.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Final Thoughts

When we say that childhood ADHD traits or self-control challenges are associated with adult illness or shortened lifespan, we are not talking about destiny. We are talking about probability shaped by environment over time.

And probabilities change when people understand their bodies differently.

These papers do not close the story. They open it.

And they invite a question that feels very Rebis to us:

If early traits shape adult bodies, what happens when we intervene earlier—not just with labels or medications, but with form, function, breathing, sleep, structure, and understanding?

That’s not a conclusion.

We feel it’s a very good place for the collaborative conversation to begin.

Kind mojo,

Kev & Dave

Kevin Boyd, DDS, MSC

Chief Dental Officer, Rebis Health

David E. McCarty, MD, FAASM

Chief Medical Officer, Rebis Health

Co-Creator (with Ellen Stothard, PhD) of the Empowered Sleep Apnea project

References